Living abroad, “I love Mexico City” is the most common response I get when I tell people I am from CDMX. It was not until recently, however, that somebody pointed to me that to some tourists, the very Mexico City that they love is limited to only a handful of neighborhoods.

Dear reader: this is a bit longer-than-usual Substack on an issue that received a lot of attention worldwide. My intention with this article is to describe the gentrification in some neighborhoods of Mexico City and use data to illustrate the issue. Over the years, gentrification has spilled into many neighborhoods of the city, but the epicenter remains the same. As I was writing this article, I realized that this could be a long research essay, but wanted to keep it succinct and focalized within reason. This article is also available in Spanish here.

Growing up in Mexico City, I quickly learned that protests in the city were fairly common. The country’s capital, formerly known as the Federal District, is home to most Federal Government entities, Congress of the Union and the Judicial branch in addition to its own local institutions. This means that any public discontent towards a national or local development will be followed by some type of demonstration or large protest in the capital.

Mexico City, commonly known as CDMX, is massive despite having the smallest surface area among the country’s 32 states. The city is home to 9.21 million people (7% of the country’s population), has a population density of 6,163 inhabitants per square kilometer and contributes 15% of the country’s economic output.1 Millions of tourists visit the city each year to enjoy what it has to offer: culture, history, food, music, vibrant nightlife and so on. However, the capital has its fair share of challenges, including bad air quality, bad traffic, water shortages, public safety issues and a growing housing crisis.

A quick summary of the anti-gentrification protests in Mexico City.

In July 2025, Mexico City experienced a wave of anti-gentrification protests targeting rising rents, real estate speculation and the displacement of local residents in parts of the city. The first protest (07/04) in the trendy areas of Roma and Condesa coincided with U.S. Independence Day and escalated to vandalism and anti-American messages. A second demonstration (07/20) in the southern area of Tlalpan resulted in damage to cultural sites and anti-foreign slogans. The real estate speculation caused by the upcoming 2026 FIFA World Cup largely motivated this protest. The third and final protest (07/26) was around the Centro Histórico and more peaceful. For this protest, the U.S. Embassy issued a security alert ahead of it, warning of potential violence based on the acts observed during the previous ones.

The three July 2025 protests in Mexico City were fueled by an issue that literally hit home for many residents: a surge in the cost of living in parts of the city. This has already transformed the city’s economic dynamic in the last five years and could potentially intensify due to the upcoming FIFA World Cup 2026. The Estadio Azteca, located in southern Mexico City, will host five games, including the inaugural match. The thousands of tourists attracted by this event will need a place to stay and will likely seek alternatives to hotels such as Airbnb and VRBO.

The demonstrations were officially portrayed as anti-gentrification protests. Understanding the concept of gentrification is important to put in perspective what is happening in Mexico City and other cities nationwide and worldwide. Hence, this Substack will explore the issue of gentrification in the context of Mexico City and analyze the main drivers behind it.

This Substack is structured as follows. The first section introduces the issue of gentrification using Mexico City as an example. The second section summarizes major events that contributed to the arrival of “digital nomads” and other remote workers in Mexico City. The third section discusses the main causes of the protests, including my own analysis using official data. The fourth section summarizes the measures announced by the government to contain the effects of gentrification. Finally, the fifth section concludes with my reflections on this issue.

1. Gentrification for dummies

The term gentrification was coined in 1964 by sociologist and urbanist Ruth Glass. Glass used this term to capture the (economic, demographic, commercial, cultural, and physical) transformation of many central London neighborhoods. In particular, she noted that “the social status of many residential areas is being uplifted as the middle class, or the gentry, moved into working-class space, taking up residence, opening businesses and lobbying for infrastructure improvements.”2

In present times, the term is often used to describe the physical displacement of a vulnerable segment of the population by one with greater purchasing power. This displacement tends to be accompanied by changes in the “vibe” of a given location (think about coffee shops, yoga studios and fancy vintage shops), which are not necessarily bad per-se but put the displaced population in a more precarious situation.

According to Glass in her work about London, new urban aspirations, urban renewal and rising commuting costs incentivized the middle-class to move into disinvested neighborhoods.3 What is happening in Mexico City is not too distant from what Glass described in London. In this case, however, neighborhoods in the central alcaldía of Cuauhtémoc are seeing a large influx of foreigners, including digital nomads and other remote workers, who find this area appealing enough to lay temporary roots.

The Condesa and Roma areas are particularly attractive for this crowd. These are cool neighborhoods where tourists feel safe and comfortable. These neighborhoods have walkable sidewalks, bike lanes, various green areas, pet-friendly shops, refurbished apartment buildings, fancy coffee/tea shops with wi-fi and a wide variety of restaurants serving instagrammable dishes. It is normal to see large groups of tourists and hear a good amount of English and few other Romance languages. To some it might feel like they are in a different country. But of course, they are in Mexico, there are a good number of Mexicans around and the food is great. These areas are just becoming increasingly inaccessible to many locals.

2. Understanding the large influx of digital nomads to Mexico City

Every other Saturday in the early 2000s my family used to go for breakfast in the Condesa area, buy popsicles at La Pantera Fresca and walk for a couple hours around Amsterdam and Parque Mexico.4 I always thought this area was charming and different from other fancy areas like Polanco, Lomas de Chapultepec or Bosques de las Lomas. There were a lot of small restaurants and cafés, you did not need a car to move around and you could sit at a park bench watching dogs run around – it was a good mix of commercial, residential and public spaces. The apartment buildings were old but seemed spacious and cozy from the outside. There were some tourists here and there enjoying the vibe. Even back then it was a desirable location.

When comparing Condesa and Roma in the 2000s against recent years, the most notable change to me is the demographic shift. It is very common to see young people working remotely from here. Most of these newcomers, often called digital nomads, come from abroad and face little to-no-restrictions to enter Mexico, earn in foreign currency and can afford the soaring cost of living. Some stay for a couple of weeks while others stay for months. With less permanent residents and more temporary residents, the dynamic in these areas became different. Apartment buildings previously occupied by middle-class families are now occupied by numerous digital nomads coming in and out, justifying the zones’ higher rent and more expensive lifestyle.

Cambridge dictionary defines a digital nomad as someone who does not have a permanent office or home and works from different countries, towns, or buildings using the internet.

The COVID-19 pandemic was a key catalyst for gentrification in trendy neighborhoods of Mexico City. Most people started working remotely and some discovered they could do their job from a different country, granted they had a laptop and wi-fi. Unlike many countries, Mexico had very loose restrictions for international travelers. The country’s rich culture, warmth, proximity to the United States and a favorable exchange rate made it an excellent choice for digital nomads. At that time, Mexico City’s relatively low cost of living lured tourists, particularly Americans, earning in foreign currency who could afford to rent Airbnbs and live comfortably in these areas.

This trend was further exacerbated by an agreement signed in October 2022 between Mexico City's government, Airbnb and UNESCO. This agreement effectively endorsed the digital nomad lifestyle by opening Mexico City to anybody, foreign or national, with a remote job that could afford an Airbnb. Naturally, these newcomers chose the central alcaldía of Cuauhtémoc, where the largest concentration of Airbnbs are located.5 Many apartment buildings shifted from traditional living units to more profitable Airbnb units.

The agreement’s stated goal was to “promote the city as a global hub for remote workers and develop and showcase cultural and creative stays and experiences on Airbnb that enhance Mexico City’s reputation as the Capital of Creative Tourism.”

Like COVID-19, word of mouth spread quickly and eventually thousands of digital nomads made their way into the Roma and Condesa areas, which drove rent and property prices up. Facing a higher cost of living, people started to move out (mostly forced out) and some businesses closed up shop. The old apartment buildings with a handful of units per floor were replaced by refurbished buildings with smaller units advertised for digital nomads and other travelers.6 New businesses targeting the new demographic started to open. It was only a matter of time before the affected population took the issue to the streets.

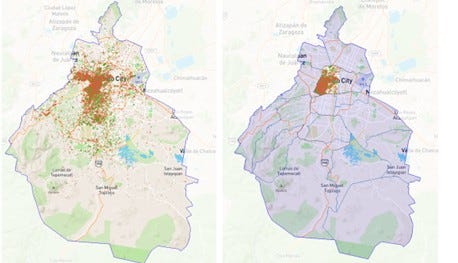

The maps below show how Airbnb7 rentals are concentrated in the central areas of Mexico City (left), most notably in the alcaldía Cuauhtémoc (right).8

3. Unpacking the surge in rent and property prices and the role of Airbnb

At the heart of the anti-gentrification protests was the people’s discomfort with higher property and rent prices. Mexico City is the state with the largest share of rental homes in the country, with approximately 44% of 2.72 million dwellings in the city classified as occupied rentals (national average is 32%).910

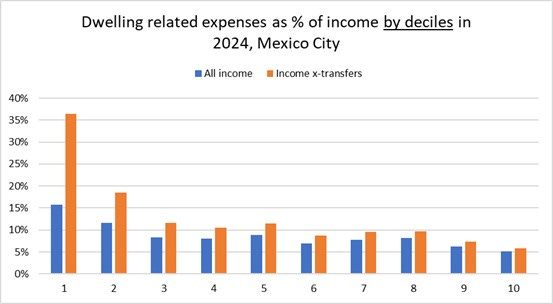

Changes in rent prices affect the thousands of families living in the 1.39 million rental dwellings. In Mexico City, on average, households spend about 9% of their income on dwelling related expenses, including rent and services (national average is 7%). This proportion, however, varies according to income, reaching an average of 27% for the lowest two income deciles and as little as 6% for the highest deciles.11 This means that changes in rent will disproportionally affect the most vulnerable families. The graph below illustrates this variation.

Evidence from country-wide United States, New York City, Barcelona, Buenos Aires, Lisbon and Porto show that short-term rentals such as Airbnb could increase house prices and rents. While rents increase for various reasons, the displacement of longer-term rentals by shorter-term rentals appears to be a key reason behind the surge in house prices and rents in the alcaldía Cuauhtémoc.12 This adds to the ongoing housing crisis in Mexico City. In principle, a decrease in the supply of longer-term rentals while holding constant the demand for longer-term rentals will result in a higher rent price.

Below is a high-level analysis showing how rents have increased, how the number of certain dwellings has fallen and how Airbnb listings have boomed in key areas of the alcaldía Cuauhtémoc.

Dwellings have become more expensive in Mexico City, but some areas have witnessed greater appreciation. Among alcaldías considered in the Federal Mortgage Corporation’s (SHF) dwelling price index, Cuauhtémoc registered the highest price increases, consistently beating Mexico City’s and its Metro Area’s average hikes.13 The graph below illustrates how the price has increased in Mexico City, the Mexico City Metropolitan Area and select alcaldías over the last years.

Rents have also increased significantly. According to data from Numbeo, the average monthly rent for a 1-bedroom apartment in the city center rose from $12,671 pesos (US$589) in 2020 to $19,167 pesos (US$1,046) in 2024, while monthly rent for an equivalent apartment outside the city center increased from $7,366 pesos (US$343) to $11,569 pesos (US$631) in the same period.14 For reference, an average formal worker in Mexico City earned a monthly salary of $15,666 pesos (US$729) in 2020 and $22,463 pesos (US$1,226) in 2024, while an informal worker15 very likely earns below this average.1617 This shows that rents in central areas of the city are becoming increasingly unaffordable for many segments of the population.

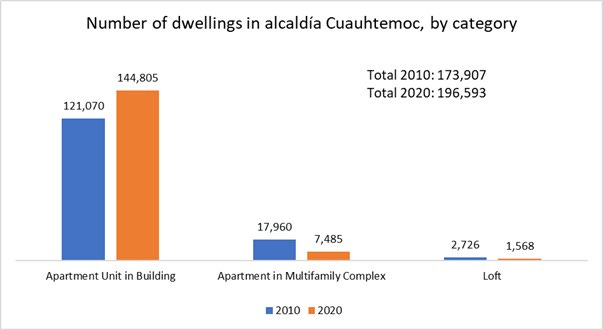

Zooming into the alcaldía Cuauhtémoc, there was a shift in the types of dwellings in the area. Between 2010 and 2020, the number of dwellings located in multifamily apartment complexes (vecindades) which are a traditional setup for lower income or working-class households fell by more than half. The number of dwellings registered as lofts also decreased considerably in the same period. Meanwhile, the number of apartment units rose by one-fifth. This hints at a possible displacement of families out of the vecinades (where more modern apartment buildings have been built) as well as a repurpose of lofts for apartments or even Airbnbs or similar platforms. The strong prevalence of apartment units in the area, coupled with the increase in rent prices seen in recent years suggest that higher income individuals/families are populating these neighborhoods.

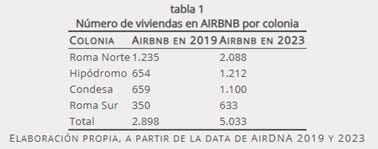

Many of these new apartment units are being used as Airbnbs. The strong influx of digital nomads into the alcaldía Cuauhtémoc, specifically into trendy areas like Roma and Condesa, has been enabled by platforms such as Airbnb. The supply of Airbnbs has increased to meet the growing demand for temporary homestays by both traditional tourists and remote workers. This growth has also been accompanied by a significant change in the platform's model. Initially, it was individuals renting out private bedrooms or apartments, but the platform is now dominated by businesses and groups with multiple listings. This shift from a service of the "sharing economy" to one of a commercialized real estate market is evident as many apartment buildings have been repurposed to serve as clusters of short-term rentals.

Using data from AirDNA, this paper shows that the number of Airbnb listings in Roma and Condesa almost doubled between 2019 and 2023, and it is likely that the figure continues to increase.

The following section summarizes the measures announced by the government of Mexico City to address the surge in rents, lack of affordable housing and the explosive growth of temporary homestays.

4. Authorities’ response to the issues raised by the protests

Days before the second anti-gentrification protest took place, the government of Mexico City announced the “Bando 1” strategy comprised of 14 actions.

The proposed measures aim to guarantee access to decent and affordable housing in Mexico City, while protecting local communities and balancing the rights of landlords and tenants. The city government intends to impose a cap on annual rent increases to prevent them from exceeding the inflation rate. It also plans to implement stricter regulations on short-term rentals like Airbnb. Authorities have committed to building new public rental units to increase the supply of affordable housing, and to creating a new public office to provide legal support to those affected by illegal evictions. The city government will be hosting consultations with affected groups and other residents of Mexico City to design the inclusive anti-gentrification legislation/reform.18

It is worth noting that in 2024, Mexico City's Congress approved a series of reforms to the city’s Tourism Law, Housing Law and the Law for the Integral Reconstruction of Mexico City. With this reforms package, called the “Airbnb Law,” authorities tried to level the playing field between short-term rentals and traditional hotels.19 However, Airbnb and some property owners challenged these reforms and, at the time of writing, there has been no progress on their implementation.

In any case, the issue of soaring home prices and rents will continue to intensify in the coming months. Mexico City’s very own Estadio Azteca will host five games of the 2026 FIFA World Cup, including the inaugural match on June 11. About 5.5 million tourists are expected to arrive in the country, split between Mexico City and Guadalajara and Monterrey, the two other cities hosting games. Property owners and real estate speculators are already pressuring the market, leading to rising rents and property values, particularly in areas near the stadium.

The government of Mexico City might have good intentions to curb the soaring home prices and rents, but it is unclear whether they will deliver on the promised actions. The blockage of the 2024 reforms package by Airbnb shows that the global corporation and its allies will not go down without fighting.

5. Spicy Food for Thought

After researching gentrification, studying the anti-gentrification protests and analyzing economic trends in Mexico City, one thing is very clear now: gentrification cannot be stopped once it is in effect. At least not by conventional means. From a policy standpoint, I see two extremes in the solution spectrum. One extreme is to ban short-term rentals platforms and redirect public resources to reconfigure the affected neighborhoods. The other extreme is to intervene so aggressively in the market that it is no longer appealing to list short-term rentals. Both are costly and unpopular measures, unlikely to be pursued by any government.

Gentrification is a fascinating and complex policy issue. It is like a curse that inevitably shadows the footsteps of progress in the world’s most dynamic cities. It is both the symptom and the consequence of urban desirability. It is a phenomenon that flourishes where people want to live, visit and invest. Containing its negative effects will require major joint efforts from the government, private sector and civil society to find lasting solutions.

The most recent measures announced by the government are a step in the right direction, but some concessions must be made by all parties to reach a consensus. There is no unilateral way to solve this policy issue. Additionally, digital nomads and other foreign newcomers could try to engage more with the culture, try to learn the language and interact with the local communities.

One thing that blew my mind is how gentrification also changes food and restaurants. Indeed, having a cafecito and restaurant dining have become more expensive in parts of the city. But the craziest part is that some taquerías have started to remove spices and hot features from their salsas to cater to the sensitive tastebuds of newcomers. Hot spices and seasoning are such a quintessential feature of Mexican cuisine that we joke about foreigners catching “Moctezuma’s revenge.” A wide variety of salsas should be made available for customers to decide, but in some stands, only non-spicy ones are available.

If only the solution to the problems caused by gentrification was as simple as offering spicy and non-spicy salsas in taquerías…

Thanks for taking the time to read this whole article! If you enjoyed reading it or learned something new, please subscribe using the link below.

Please feel free to share my publication to help me grow.

You can also send me a DM to let me know your thoughts on my publication or if you have any requests for topics at the intersection of economics and public policy.

With information from the national statistics agency (INEGI).

Brown-Saracino, Japonica. (2013). Gentrification. https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/display/document/obo-9780199756384/obo-9780199756384-0074.xml

Idem.

Some days we would also walk around Parque España, but Parque México was a must.

It is worth noting that other neighborhoods, such as Escandón (in Miguel Hidalgo) and Doctores (in Cuauhtémoc) have become increasingly popular.

The government of Mexico City has a dedicated portal for digital nomads in the city. This is part of the local government’s efforts to position the city as a global hub for remote workers. In this online one-stop shop, people can read about key aspects of relocating to the city, including information about visas, housing and utilities.

Short-term rental platforms, like Airbnb, are online services that connect people looking to rent out their property (hosts) with travelers seeking a place to stay (guests). Unlike traditional hotels, these platforms facilitate the rental of everything from a single room to an entire home for short periods of time.

Historical data for Airbnb listings is not readily available online. One has to request and, depending on the type of request, pay for it. Of all data providers I found, Inside Airbnb provides the most useful visuals. Ideally, I would have also the maps with listings from 2020 (or before) to provide a visual representation of the surge of Airbnbs in the city.

El Informador. (2022). ¿Quiénes son las personas que más rentan vivienda en México? https://www.informador.mx/economia/Infonavit-Mexico-Quienes-son-las-personas-que-mas-rentan-vivienda-y-en-que-estados-del-pais-20221214-0038.html

According to the 2020 National Housing Survey, there were approximately 2.72 million dwellings in Mexico City, of which 1.39 million were inhabited by the owners. The remaining dwellings (1.32 million or about 49%) is estimated to be rental or borrowed, or in some dispute. The 44% corresponds to only rentals, according to the source noted. The 5 percentage point difference is assumed to be borrowed homes or in some dispute.

This was calculated by taking the ratio between average quarterly expenses and income provided by households in the 2024 National Survey of Household Income and Expenditure (INEGI-ENIGH). The figures reported in the paragraph take into account all income reported by households.

Reasons could be specific to the property (e.g., appreciation, improvements or maintenance) or to the neighborhood (e.g., derived from favorable developments in the area or from public policies).

This is an index that shows changes in home prices. For more information, see here (site in Spanish).

Figures in pesos as reported by Numbeo.

In end-2024, the rate of informality in Mexico City was 45.5% (source: INEGI-ENOE).

Figures in pesos were converted to U.S. dollars using the average FIX exchange rate for each year, published by the central bank.

Notable measures include creating the Host Registry, limiting the annual occupancy of short term rentals to 180 days per year and prohibiting the use of properties under social housing, affordable housing, or reconstruction programs for short-term rentals. A summary of the changes can be found here.